What is it?

Osteochondrosis is a developmental joint disorder in young animals caused by the abnormal maturation of the cartilage of immature bones into normal adult bone.

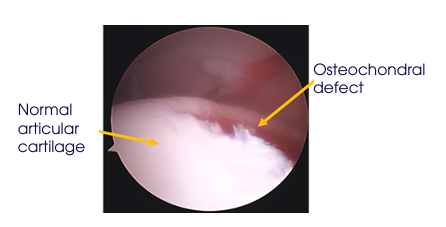

While the cause of osteochondrosis is incompletely understood, it is thought that the abnormal cartilage maturation process results in small areas of thickened, weak cartilage which can variably fissure (“crack”), forming a raised “flap” of cartilage which may later break off within the joint.

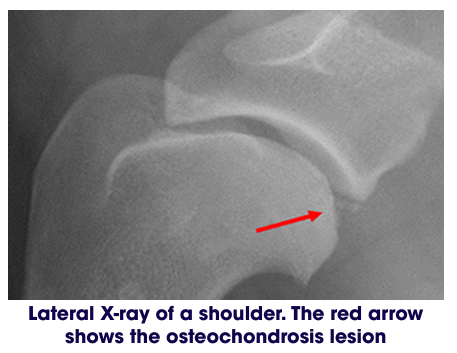

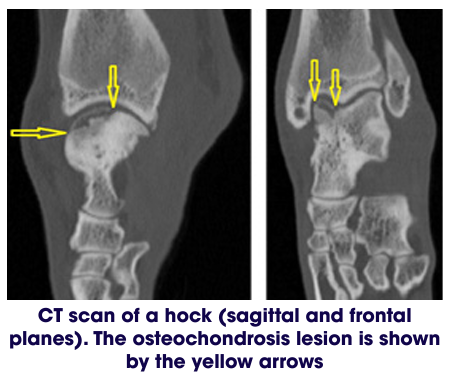

Joints affected can include the shoulder, elbow, stifle (knee) and hock (ankle).

Osteoarthritis later develops secondary to osteochondrosis.

Clinical Signs

Large and giant breed dogs are predisposed, whereas osteochondrosis is rare in cats.

Clinical signs typically occur at approximately five to eight months of age, and include lameness and stiffness that tends to be worse following exercise, disuse muscle loss and pain on manipulation of the affected joint.

Older animals may demonstrate signs of lameness associated with the osteoarthritis that has developed secondary to osteochondrosis, but may not have had signs of lameness directly associated with osteochondrosis when they were younger.

How is osteochondrosis diagnosed?

Following orthopaedic assessment, your dog will need to have sedation or general anaesthesia for X-rays and often a CT scan. Joint taps may also be performed.

Conservative Treatment

Conservative or non surgical treatment of osteochondrosis is suggested for young patients with minimal lameness, or older patients with advanced secondary arthritis, where a significant benefit of cartilage flap removal is less likely. Conservative management consists of:

• Exercise modification

Exercise level will need to be modified to a level which does not exacerbate the lameness associated with osteochondrosis and later, secondary osteoarthritis. During a painful period when osteochondrosis signs have flared up, exercise will need to be reduced, but still include short periods of regular on lead exercise to help reduce the joint “stiffening up.” In periods where signs are well controlled, exercise can be increased, and adapted to suit what the individual pet can manage comfortably. Excessive exercise or activities which exacerbate lameness should be avoided.

• Pain relief

There are many types of pain killers that can be used to reduce the discomfort of joint pain. The frequency and types of medications used should be adapted to the individual pet, and to the severity of joint pain as signs fluctuate. It will be discussed on an individual basis.

Pain killers may be prescribed for use on a “bad day” when osteochondrosis / osteoarthritis signs are briefly worsened (e.g. after excessive exercise), as a short course of medication (often followed by a recheck appointment to check progress) or as an ongoing medication. There are potential side effects of all medications, and pets on ongoing medications should have regular prescription checks to ensure that their medications meet their current requirements, and that the benefit of taking them outweighs the risk of side effects. For pets with complex pain relief requirements, appointments with a pain specialist can be made with the Small Animal Referral Hospital’s Pain Clinic.

Weight Management

Maintaining the correct, or slightly lean, body weight is important to reduce the weight carried through the joints and to minimise the progression of secondary osteoarthritis.

What could go wrong?

Surgical treatment is usually straightforward and complications are rare. However complications occasionally occur and they include swelling or seroma formation and infection. Lameness may persist as a result of failure to remove all the flap, or due to osteoarthritis or the presence of severe large and deep lesions.

What is the likely outcome for a dog with osteochondrosis?

It is important to understand that surgery is not curative. The aim of surgery is to alleviate lameness and improve the dog’s quality of life.

The outcome of osteochondrosis treatment often depends on the joint affected. Dogs with shoulder osteochondrosis appear to be more likely to have a favourable outcome following surgery despite development of osteoarthritis in the joint, and many dogs with elbow osteochondrosis have a good to fair outcome with conservative treatment. The outcome for dogs with stifle osteochondrosis is unpredictable, and the outcome for hock osteochondrosis appears to be guarded, with a degree of lameness often persisting.

Exercise restriction

Following surgery it is essential for your pet to be rested whilst the bones and soft tissues heal. You will be given specific instructions tailored for your dog on your personalised discharge sheet.

Generally for small-medium dogs we recommend crate rest. Larger dogs may be confined to a crate or a small room or a pen, if you do not already have a crate now is the time to start organising this. Exercise is usually restricted to short lead walks several times a day for a period of time.

Wound care:

Following surgery the skin incision(s) should be checked twice daily for two weeks or until the skin sutures have been removed. Licking or chewing of the surgical site can cause infection, and so we recommend that a buster collar be worn until the skin sutures are removed. If discharge or increased swelling is noted you should contact us and an examination may be necessary. Your dog may have been sent home with a small dressing in place over the incision. This can be left in place as long as it is clean and functional.

Physiotherapy and hydrotherapy:

Physiotherapy can be very beneficial for recovery following orthopaedic surgery. Where appropriate we will provide separate physiotherapy instructions.